Mt. Osceola Trail

Mt. Osceola 4340 ft

When I hiked East Osceola with Luna last March, I fully intended to summit both peaks. After trying (and failing) to find a way around the icy rock chimney, we had to throw in the towel on Mt. Osceola. It was one of the more frustrating u-turns I’ve had to make. The second peak was less than a mile ahead, but there was no possible way to get Luna up or around that chimney. I decided to hike in from the other side, which doesn’t involve the chimney (it is between the two peaks), and to bring Luna with me again. It was Oscelola redemption for both of us.

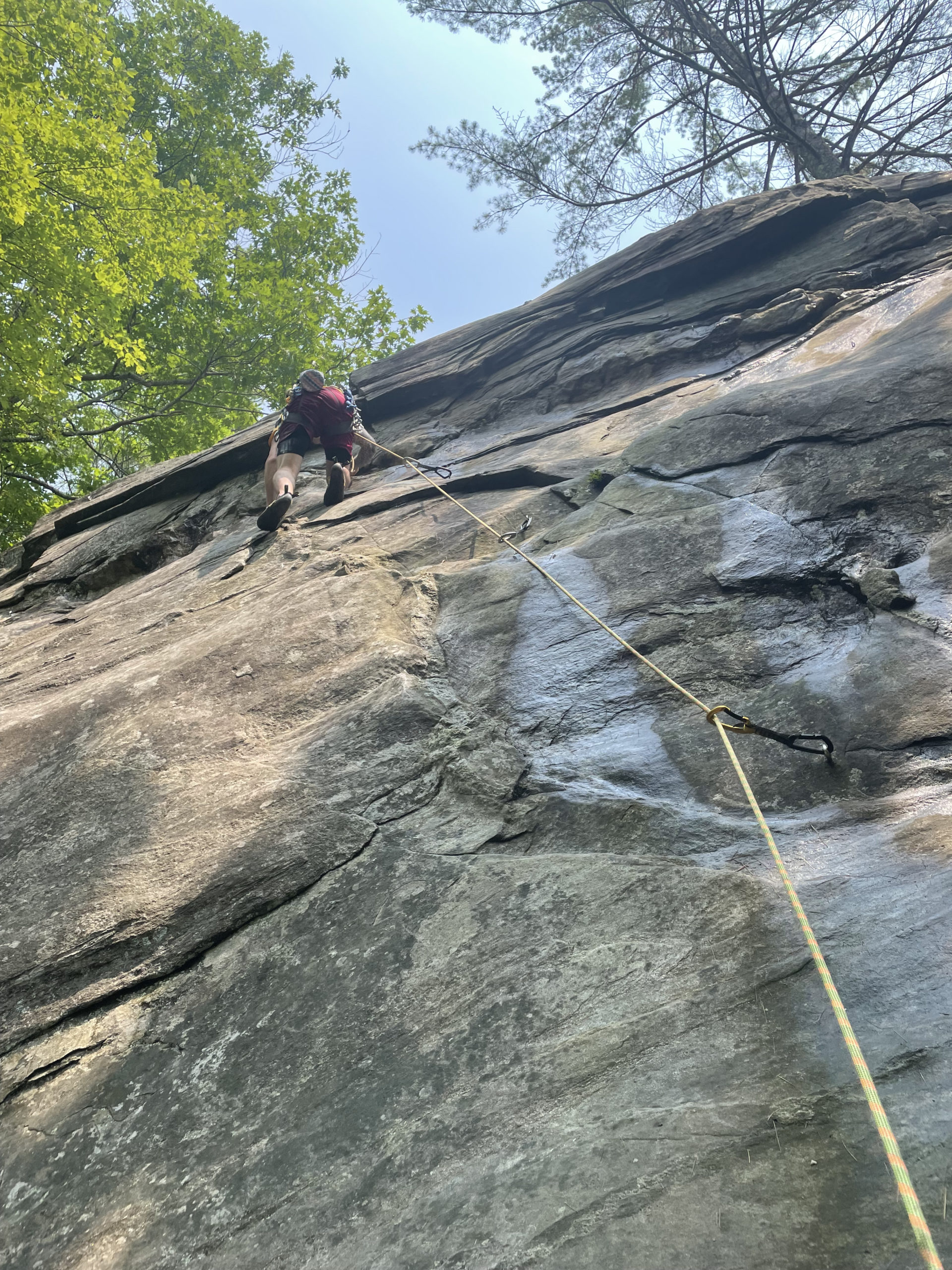

We started our adventure with an outdoor climbing day at Rumney Rocks. There’s enough to say about this incredible place for a separate post. For now, I’ll say it is one of the premier sport climbing destinations in the country, supported by an awesome non-profit local organization called The Rumney Climbers’ Association.

The day we went the crag were pretty wet, so the climbing was limited. It was my first time at Rumney, and it was nice to just see what this legendary spot was all about. After messing around on the rocks, we camped the night with our friend Max. A pretty major thunderstorm came through overnight… major enough that we all took shelter in Max’s van. Luckily the storm passed without causing any real damage and Luna and I were able to move back into our tent. It did get me thinking, though, about what I would do if I didn’t have a safe, dry vehicle to hop into.

The experts on lightning safety agree: No place outdoors is safe. BUT… there are plenty of things you can do to reduce risk of injury or death (hallelujah). The National Weather Service provides a highly informative PDF regarding backcountry lightning risk management. Before diving into that, let’s brush up on thunder-and-lightning 101.

What is lightning?

A giant spark of electricity in the atmosphere between clouds, the air, or the ground.

What is thunder?

The sound caused by a nearby lightning flash. Lightning heats the air and causes it to expand. Immediately after the flash, the air cools and contracts quickly. This rapid expansion and contraction creates the sound wave that we hear as thunder.

The National Weather Service says if you can hear thunder, lightning is close enough to strike you, whether you can see it or not.

- For every five seconds that pass between seeing lightning and hearing thunder, the storm is one mile away.

- Lightning tends to strike tall objects, which is why trees are often hit… and why standing near a tree or out in the open during a storm is so dangerous.

- Most lightning strike victims are in open areas or near a tree.

- Trees hit by lightning frequently explode or burst into flames, which is another good reason to keep your distance from them during a storm.

- Most closed cars are safe from lightning. When lightning strikes a vehicle, the car acts as a Faraday cage, causing the electrical current to travel around the outside of the car’s metal frame into the ground. Don’t lean on doors or touch handles during a thunderstorm.

- Don’t stand in water or touch metal. Water and metal don’t attract lightning, they are excellent conductors of electricity.

- Although it can strike in any season, lightning is most common during summer thunderstorms (aka prime camping season).

So, what do you do if you’re stuck outside in a storm?

If you’re able to get to shelter before the storm is overhead, do it. A vehicle or a building with electricity or plumbing (like a campground bathroom) are your safest choices. Outhouses and picnic shelters are NOT good options because there is no way to ground the electricity if the structure gets hit.

Okay, great, now what if you’re backpacking in the woods and there is no shelter?

Well, it comes as no shock that the worst possible place to be in a thunder and lightning storm is on an exposed ridge. Get off the ridge at the first sign of a storm.

If you’re pitching a tent, the best place to do it is in a low-lying area, but not one that could flood. Remember that tents offer zero protection from lightning, and if your tent is old school with aluminum or metal poles, you’re better off not pitching it at all since those poles will attract lightning.

Assuming your tent is a newer model and you’ve found a safe place to put it, make sure you also consider widow-maker trees (ie trees with dead or weak branches that could fall on your tent). The other major hazards are wind (in very high winds, tents can be lifted up with people inside them) and water (if everything gets wet is it cold enough for hypothermia?). If your location is relatively safe, staying in the tent versus leaving it is the same risk, but you’ll be drier in the tent.

If you don’t have a tent or don’t have time to pitch it, then what?

Definitely don’t take shelter in a cave entrance or rock overhang. Lightning travels along vertical surfaces to reach the ground. When lightning jumps a gap, any object bridging the gap can help conduct the current.

If possible, get off the windward side of the mountain (the side the storm is approaching from). Find a ravine or low lying area where you are not the tallest thing. Do NOT lie flat on the ground, which exposes your entire body to the possibility of ground current. If you are with a group, spread out to 20 foot intervals to reduce the risk of multiple injuries.

Hiker term: Ground current

When lightning strikes a tree or other object, much of the energy travels outward from the strike point, moving in and along the ground surface. Ground current causes the most lightning deaths and injuries.

Assume the lightning position!

Keep your feet together. This will significantly reduce the effect of ground current. If you’re feet are apart, the current goes up one leg, through your body, and down the other leg to exit. If you have a pack or a foam pad, get on top of it, either sitting (all body parts off the ground) or crouching (feet together). This will help insulate you from a shock.

Stay in your shelter or lightning-safe place for 30 minute after the storm passes. One third of lightning fatalities occur because people thought it was safe to leave before it was.

The bottom line… to some extent, lightning strikes are totally random. Storms are not.

According to the National Weather Service, there is no such thing as a surprise or freak storm. Weather patterns and forecasts can predict storms with extreme accuracy. That said, weather can change quickly in the mountains and storms can come up without much warning, especially if you don’t have cell service to keep an eye on the radar. Always do your weather homework before you hike, and if a storm is on the radar, time your trip to make sure you’re in a safe place when the storm hits.

Phew. Now that we’re all better prepared to survive a lightning storm in the woods, let’s get back to Mt. Osceola.

After a very wet night, we woke to a clear morning. The soaked, muddy tent got thrown in the trunk and off we went. To reach Mt. Osceola from the west side, we started on Tripoli Road, accessible off I-93. This road is seasonal, so if you’re hiking the Osceolas in the winter, you have to start on the Kancamagus side.

The Mt. Osceola Trail starts with a moderate climb and rocky footing, crossing several small brooks in the first mile. Thanks to the storm and a generally wet week, there was a lot of water on the trail. For much of the early hike we were trekking through a stream bed. After a mile the trail starts switchbacking toward the ridge and traversing numerous angled rock slabs. These are tough on the ankles due to the slope, but there is a narrow path at the bottom of the ledge where you can walk on level ground.

The final mile to the summit is a gradual climb up the ridge. It ends at a large, flat ledge, with a second big ledge a few yards further on. Both have remnants of old fire towers, the second a more recent structure with cement blocks. Although the morning had shown some promise for clear skies, the mountains were socked in with fog by the time we reached the top. The Appalachian Mountain Club White Mountains Guide reports “excellent views” from Mt. Osceola. I’ll take their word for it and hope to visit again on a clear day.

Summit lesson: Lightning is a serious threat to hiker safety if you don’t take precautions. Read up on how to prepare and what to do when a storm comes!

Mt. Osceola Trail

| Total elevation: 4340 ft | Elevation gain: 2070 ft |

| Mileage: 6.1 miles | Alpine exposure: minimal |

| Terrain: rocky footing, ledges, stream bed | Challenges: angled ledge, rough footing |

| View payoff: excellent | Dogs: yes |

Recap: This was a lovely, relatively easy hike with a nice view (on a clear day). It would be a good choice for a hiking newbie or someone getting started on the 4000 footers. There is some rough footing and potentially wet stream bed hiking, particularly if there has been a lot of rain. The angled ledges aren’t steep but they’re awkward to balance on; luckily there’s a narrow strip of ground below the ledge that offers a more even walking surface. The summit is big and flat with fire tower remains and several nice viewpoints. Bear in mind, if you choose to continue on to the East Osceola summit, this hike becomes significantly more challenging due to the terrain.

No Comments